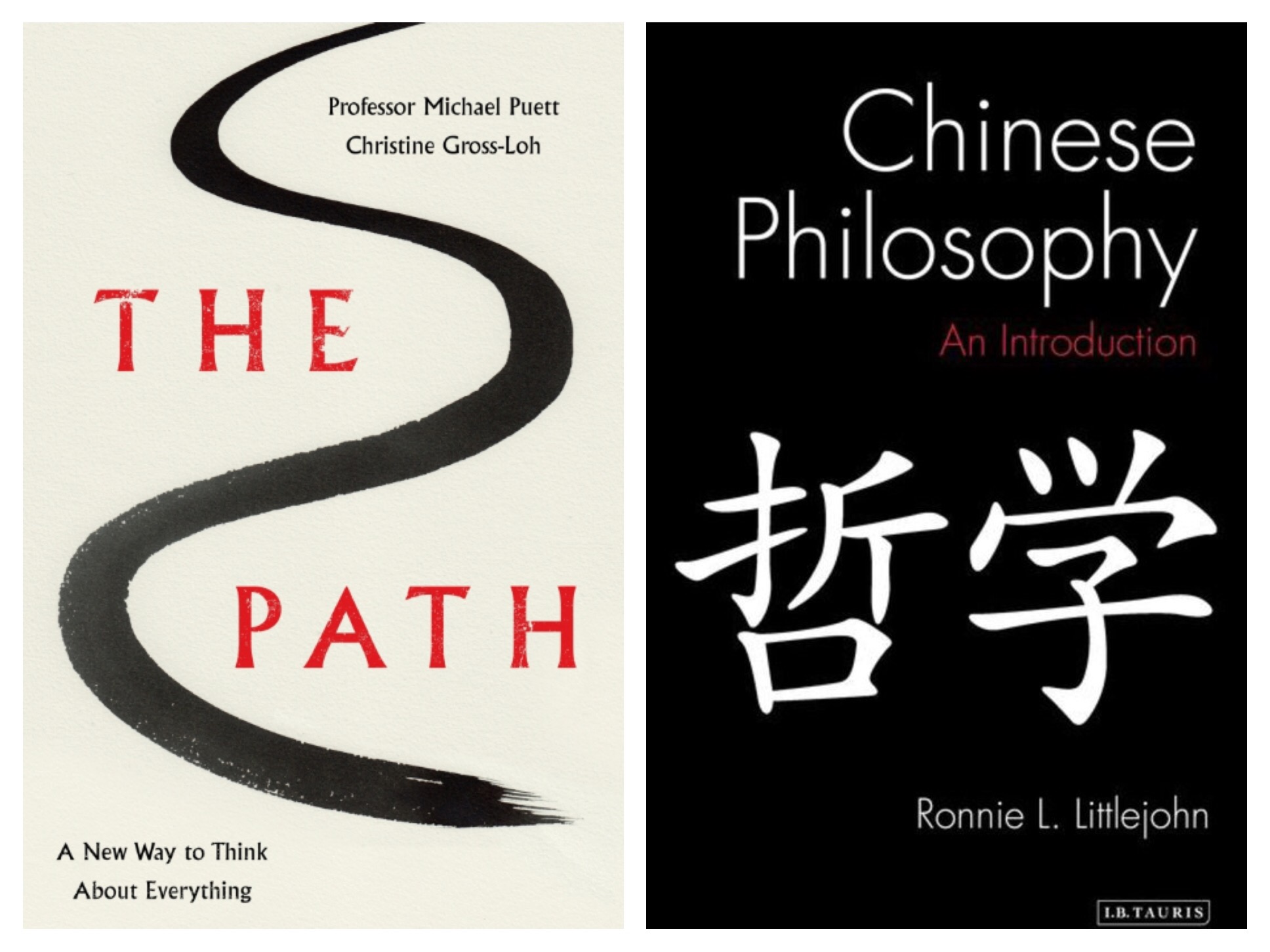

Last week I bought two new books on Chinese philosophy: The Path by Michael Puett and Christine Gross-Loh and Chinese Philosophy. An Introduction by Ronnie L. Littlejohn.

The books are both accompanied by a selection of original texts. The Path comes with a free downloadable e-book. The companion volume Chinese Philosophy: The Essential Writings is not available yet, but will be published soon.

This is where the similarities end. Both books take a completely different approach to Chinese philosophy.

The Path is a book for general readers without any previous knowledge of Chinese philosophy, based on a series of popular lectures by Harvard professor Michael Puett. More than just an introduction to Chinese philosophy it is a book for self-cultivation, aimed to show modern readers what ancient Chinese philosophers can teach us about a good life.

If you want to be inspired by Chinese philosophy in your own life, this book is an excellent starting point. Do not expect a balanced and complete account on Chinese thought. Professor Puett selected several ideas from classical Chinese teachers like Confucius, Mencius and Laozi and shows how they can offer new perspectives on our modern way of life. He also uses a lot of contemporary examples to show their relevance for us today.

In doing so he often shines a surprising new light on these classical Chinese teachers. The main point Puett makes about Confucius is his preoccupation with rituals. However, he does not portray Confucius as a conservative or a traditionalist. On the contrary, according to Puett Confucius used rituals in a new and provocative way to transform people. Confucius understood that through rituals we create “As-If” situations, alternative realities that can help us to break with old patterns and routines. “Overcoming the self and turning to ritual is how one becomes good”.

One of Puett’s main targets in his book is the western belief in an authentic and “true self”, a concept that according to him only restricts what we can become. In stead of searching for an authentic self, Chinese thinkers always took our surroundings as a starting point for self-cultivation. They teach us that we can cultivate ourselves continuously through connections and interactions with the world around us.

I really enjoyed reading The Path. It reminded me of Professor Yu Dan Explains the Analects of Confucius, another book that aims to make classical Chinese thought accessible to a broad audience. This book is based on lectures for the Chinese television and sold millions of copies in China and around the world.

Yu Dan is often criticised for her popular approach to Chinese philosophy and it is to be expected that Puett will soon receive similar criticisms from various specialists of Chinese philosophy. Such criticisms may be right or not, but in their lectures and books Puett and Yu Dan do exactly what the Chinese philosophers themselves intended to do: to educate people.

In Chinese Philosophy. An Introduction Ronnie L. Littlejohn takes a pure academic approach. The purpose of Littlejohn is not to educate his readers but to help them “understand how Chinese philosophers approach philosophical questions and what positions they take”. In his book he explores the historical, political and cultural significance of key texts, thinkers and movements from classical times to the present.

Littlejohn does not follow a chronological order, but he grouped philosophical questions into four thematic chapters: ontology, epistemology, ethics and political theory. In this way he is able to introduce Chinese concepts into existing debates of the (mostly western) philosophical academic world. This approach also has its disadvantages. The thematic division makes it more difficult to get a complete picture of a particular thinker or school.

Chinese Philosophy. An Introduction is certainly not an easy-reader (like The Path). For a book of less than 300 pages it touches upon a lot of topics and discussions. This is of course a great achievement in itself, but the explanations are often concise and difficult to follow for the general reader. On the other hand, the book is full of references that make the book very useful for further exploration. The forthcoming companion volume with essential writings will probably be very helpful as well.

In their own way, both books are good introductions to Chinese thinking. If you want inspiration for your own life, then The Path is a good start. If you want to learn about Chinese philosophy from a strictly historical or academic perspective, then Chinese Philosophy. An Introduction is probably the most up-to-date starting point.

I always read texts of ancient wisdom or philosophy from two perspectives: what do these texts say about the writer and the times they were written and then, more directly, I also ask myself what do these texts teach me? If you want to approach Chinese philosophy in these two ways, you can read Puett and Littlejohn side by side, no matter what these two authors themselves or others might think about that.