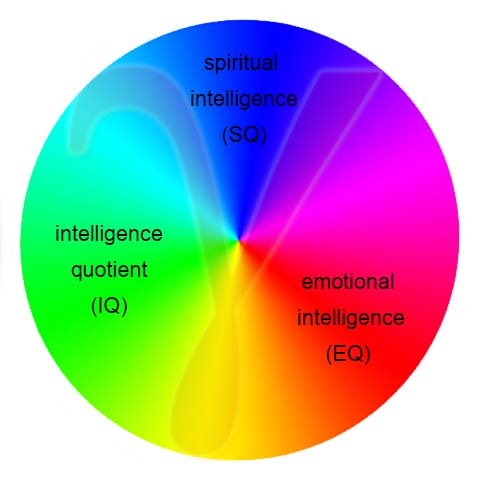

Developing a wisdom mindset involves IQ, emotional intelligence and spiritual intelligence. An illustration posted here in 2015 shows how spiritual intelligence is integrated in the Gamma Tao. The illustration shows human intelligence as an interactive continuum in which we can distinguish specialised faculties.

IQ and emotional intelligence are established concepts to describe and even measure specific mental abilities, but what is spiritual intelligence? I have always left it open to imagination, but now Mark Vernon has written a new book about it: Spiritual Intelligence in Seven Steps.

I discovered Mark Vernon on YouTube through his regular dialogues with Rupert Sheldrake and in 2021 I bought his book Dante’s Divina Commedia. A Guide for the Spiritual Journey, an excellent companion to this medieval masterpiece.

Human intelligence vs AI

His new book on spiritual intelligence was initiated during an interdisciplinary project on artificial and human intelligence organized by the International Society for Science and Religion. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has invaded our daily lives in many ways and our dependence on AI algorithms will only grow, if we want to make sense of all the data available to us. These days we marvel at the the capacity of ChatGPT to answer all the questions we have. What role can human intelligence still play in the face of so much computing power?

Mark Vernon, while embracing these new technologies, suggests that spiritual intelligence might provide an answer. He supposes that emotional intelligence could eventually be programmed into IA systems, spiritual intelligence however will remain a unique ability of Homo Spiritualis.

What is spiritual intelligence?

One of the reasons for this may be that spiritual intelligence is so hard to define, if it can or needs to be defined at all. Mark Vernon dedicates the first chapter of his book to give us an idea what spiritual intelligence might entail: a non-sensory perception or knowing “that our experience is connected to a wider vitality” that has been “given multiple names: fire, energy, soul, spirit, ground emptiness, meaning, power, Brahman, Tao, God, origen, source”.

Spiritual intelligence also gives us a direction in life. It “invites us to turn back to the ground of our being and rebuild from there”. This ground, according to Vernon, is spiritual. We are all, as Sting would sing it, “spirits in a material world”.

Perspectiva and the meta-crisis

The actual scope of the book is broader than distinguishing human intelligence from artificial intelligence. It addresses the general intellectual climate of our times, the shortcomings of scientific materialism and what has been called the “meaning crisis”.

I was pleasantly surprised to read that this book is supported by Perspectiva, a research institute that seeks to understand the relationship between systems, souls and society with a deeper understanding of the influence of our inner worlds to confront this meta-crisis.

In November 2019 Perspectiva published Iain McGilchrist’s magnum opus The Matter with Things, probably one of the most important books on philosophy of our times. More recently Perspectiva became involved in the legacy of Rebel Wisdom, a YouTube channel and community that I have followed since the start. I was present at their “Last Campfire” when this news was announced.

Spiritual commons

Perspectiva aims to inspire political, academic and business leaders, but Vernon, a great intellectual himself, already states at the beginning of his book that spiritual intelligence is not an elitist faculty. Spiritual intelligence also predates (organised) religion. We can turn to all wisdom traditions to find it, because all these traditions serve and seek to develop a sense of the nature of being. They are part of what Vernon calls the “spiritual commons”, an abundant cultural treasure from which we are all free to draw inspiration to live our lives.

The idea of the “spiritual commons” resonates very well with the practice of the Gamma Tao to provide a common ground for the exploration of all wisdom traditions.

Seven steps

Mark Vernon has organized his book in seven steps that turn our mind to spiritual intelligence. These steps are accompanied by a few spiritual exercises. Even though I consider Mark Vernon a kindred spirit, at times I had difficulties to follow his footsteps and to see where he was going. I will not discuss all the steps presented here, and, as Mark Vernon himself suggests, they also needn’t be read in order.

New perspective on human history

Mark Vernon’s first step is a reevaluation of the history of our human species. Vernon proposes to shift the attention from the Homo Faber, the human maker, and the utilitarian drive for survival, to the Homo Spiritualis and the quest for meaning and flourishing.

He gives special attention to the inward turn to self-awareness that took place during the Axial Age, about 2,500 years ago, both in Eastern and Western civilizations. The emerging individuality created a non-intermediated space for spiritual development in human minds, as can be exemplified by the famous Delphic maxim: Know Thyself.

Foundation of ethics

In the Gamma Tao the Golden Rule is the main foundation for ethics. The Golden Rule teaches us not to do to others what we do not want others to do to us. This is a rule that is clearly rooted in emotional intelligence.

Mark Vernon tries to steer away from ethical rules that seem to provoke so much polarization nowadays and considers spiritual intelligence a source for another type of ethics: virtue ethics.

Virtue ethics had been the main way of thinking about how to live well since at least the Axial Age until Immanual Kant “argued for a morality based on musts and oughts at the end of the eighteenth century, and Jeremy Bentham invented utilitarianism in the nineteenth”.

In making his case Vernon may sometimes attribute too much credit to spiritual intelligence. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristoteles used observations and rational intelligence to determine what constitutes a virtuous life. The Golden Rule is probably one of the best examples of an ethical concept based on individuality that appeared across cultures during the Axial Age. Still, it also seems plausible that human beings possess a direct (or spiritual) intuition for what is virtuous and what is not.

Kairos attention

In the last chapter Vernon calls for a transformation of attention, away from the trance of everyday life into a parallel world not dictated by chronos, the clock of secular time, but by kairos, the ever-present cosmic moment. Kairos attention spots the timeliness of a particular insight or instant.

This may very well be the most practical and profound piece of advice in the book. In an age of information overload and algorithms that are constantly trying to hijack our attention, we need to get back in control.

Kairos attention can guide our awareness to the present moment and its possible significance or meaning. A mindset based on kairos attention interprets what is happening differently. “One person’s chance incident is another’s telling synchronicity”.

The role of spiritual intelligence

Mark Vernon’s book makes it is easy to see how spiritual intelligence can change our way of being in the world and how it can bring meaning to our existence. In this book he has done a great job exploring its potential and special relevance for our times.

In the Gamma Tao spiritual intelligence is an integrated part of human intelligence, indispensable for developing a wisdom mindset. It is also mysterious and hard to grasp. Taken apart or above other human capacities to know and to be in the world, it can also direct us towards a spirituality without wisdom.

An intelligence should give us the capacity to distinguish between what is important or meaningful and what is not. This is something that easily gets overlooked, when it comes to spiritual intelligence.

If we start to define ourselves as Homo Spiritualis, we risk to become less sapiens in the process. If we do not want to become slaves of artificial intelligence, we will need all our capacities to feel, think and imagine working together. That said, spiritual intelligence may very well be the type of intelligence or X-factor that distinguishes us the most from AI.

To conclude and to get a fair hearing on this, we can now turn to AI itself and ask ChatGPT:

Does artificial intelligence include spiritual intelligence?

Artificial intelligence (AI) as a field of research and technology primarily focuses on the development of algorithms and systems that can perform tasks that would normally require human intelligence, such as understanding natural language, recognizing patterns, and making decisions.

As for spiritual intelligence, it is a subjective term. While it is being studied by some researchers, there is no established scientific model for it. It does not pertain to the traditional AI research and thus, is not a feature that is typically considered or developed in AI systems.

However, some researchers are looking into the possibility of creating AI systems that are capable of experiencing a sense of connectedness or understanding of something greater than themselves, although this is still very much a topic of debate and is not widely accepted by the scientific community.

It’s worth noting that the field of AI research is always evolving and there might be future developments that would include different areas of study and even spiritual intelligence, but currently it’s not something that is included in the mainstream of AI research.

We can conclude that Mark Vernon may be on to something.